Walking back along the commuter path, I decide to cut through the old train station by the bike shop. A man is stumbling next the the train, carrying two buckets. Behind him is a sleeping bag. I take off my headphones, planning on giving a polite hello to this homeless man and then being on my way.

I nod my head and say hi, and he says hi back. I get closer to the sleeping bag; there is a small girl in it. He says he brought her with him because he has to finish this job, and I tell him its a beautiful night to sleep outside. Then, we talk for an hour.

He complains to me about his work: his boss for this job is demanding it be done, but he has a house and a chimney at other locations that need to be finished too. He loves his boss at the station, but the boss doesn’t realize that he isn’t the only thing the bricklayer has to deal with.

He asks me my major, and he says he uses math a lot in his work, too. He is now a pro at estimating the number of bricks needed for any job. There is an art to this sort of estimating: you can’t sit and count exact numbers, you need a quick count fast to get the order in and start the work.

Then he pointed out the architecture to me. The old buildings had curved brick over the tops of the windows, because to close those tops you would have two guys holding brick on either side, adding more and more until the gap is closed at the top and the weight of the bricks holds it all in place. But then Carnegie and his boys figured some things out, and it was cheaper to throw a steel bar over the top of the window than it was to pay two guys to sit there all day. So now, the tops of windows are layed with straight brick across.

Pointing to an apartment complex, he says how the things they build today are very functional and practical, but they don’t have the same art and lasting value as these old builds. When he looks at this station, he thinks of all the lovers saying their goodbyes as the men rolled away to WW2. Its been there since 1904. One hundred and ten years.

He takes me to the front of the building, and shows me his favorite parts. The stone trim that stretches along the entire side of the building was all hammered out on site, probably by one artist. There was no room for error, each cut had to be right, no second chances. (We measure 4 times, he says, not like those carpenters doing it twice).

I ask him about the train, he shows me inside. One end has the owner in it, in the middle is an office for a property management place. Closest to the bike shop is the engine, and he brings me in. The entire thing was gutted: the old owners of the bike shop used it for storing inventory. (Customers are fickle, he tells me. That bike someone just bought needs to be replaced instantly, or you’ll be losing sales). He brings me to the back, and we look out the back window. He says he imagines this thing screaming 70 mph through Kentucky, so many years ago…

He explains to me how the diesel-electric engine reshaped the way people could travel in trains. Outside, he shows me the trucks: the frame with the wheels that could be swapped in and out at the station for repairs. Any one of these trucks has probably been on dozens of trains, he tells me. I look at the giant leaf springs, and he explains to me what they are, and then he takes me to his truck so I can see them on a car. He then takes me to the next car over in the parking lot, and we lay down on the ground and peek underneath and he shows me how the suspension in this Subaru is different.

We go back to where he was working, and he explains that he has to get up at 6 to get his daughter ready for school, and then he is working all day long at a few different jobs before he goes and gets her from afterschool care. We talk about the Ironman race the day before, and he talks about how crazy things can happen to the human body when it is put under so much stress, and how he’s come to that point after long days working himself.

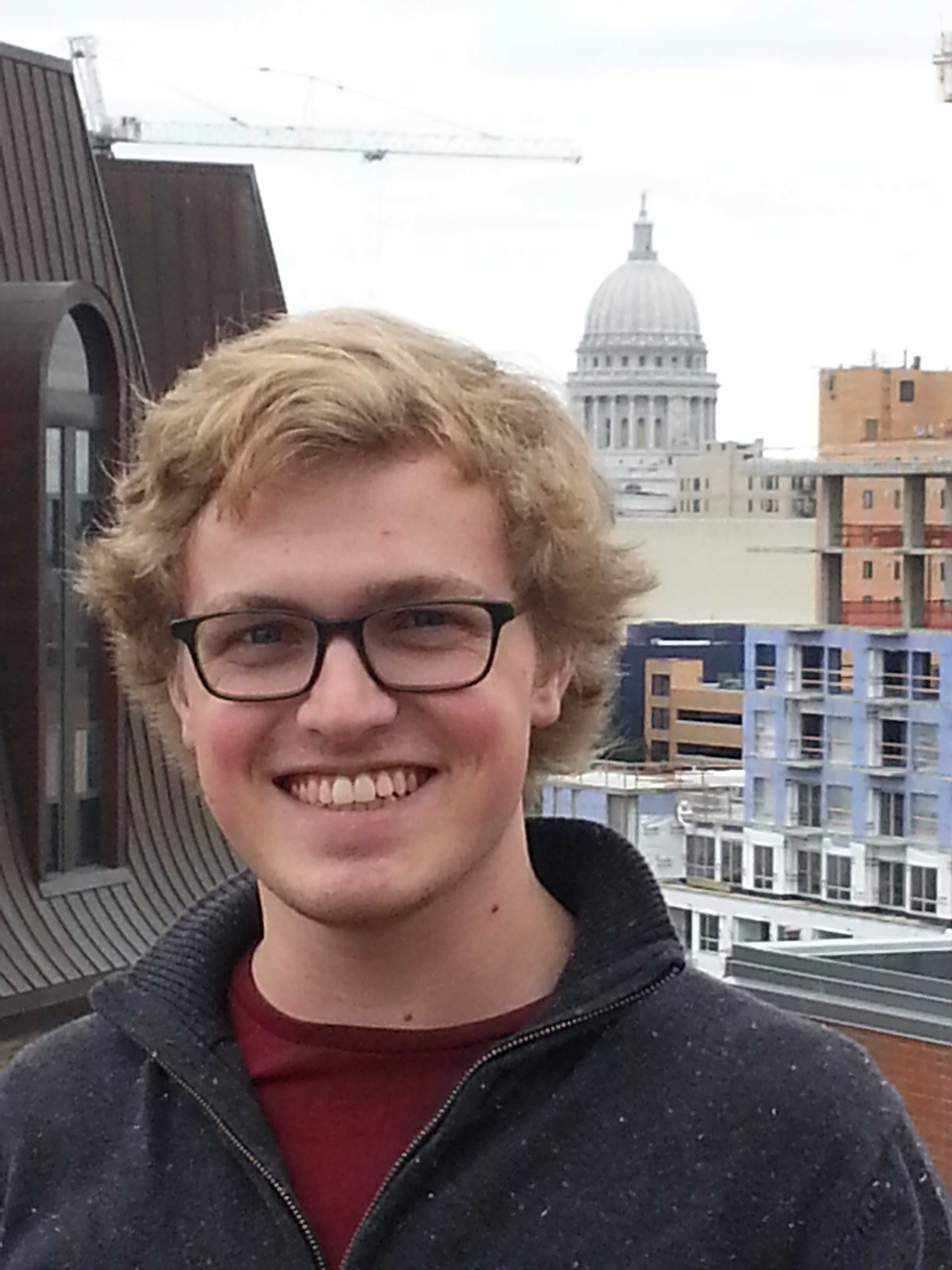

We talk about the cranes in Madison, and he tells me how they assemble and disassemble the ones here in Madison with other, larger cranes. (There are self assembling ones, but not these). He says he always befriends the crane operators, because they have a tough job up there and can’t even see what they are doing a lot of the time, and they sit all up there for an entire workday, alone.

He mentions that two bricklayers have died in Madison this year. One fell 70 feet at edgewater, and the other on a project my lake monona. He tells me of his friend that broke his back falling 60 feet, and then was back on the job 2 years later. His friend was carrying a stone with a few other guys, when the scaffolding underneath him ended, and the other guys kept going, pushing him off the scaffolding through an improperly-reinforced side railing.

I end up leaving, he says he enjoyed being able to talk to another person other than his 8-year-old daughter for a bit. I told him to keep making awesome things all around Madison (he’s worked on the train station, the kohl center, the babcock house, the capitol).

That’s when I met the bricklayer.